For the past year I have had the good fortune to legitimately engross myself in what is to me the most compelling of novels, translating Hilary Mantel’s Bring up the Bodies, the sequel to 2009 Booker Prize Winner Wolf Hall. The most compelling novels do have a habit of providing ample scope for research, leading you on winding paths outside the pages of the book in order to know what exactly an author is alluding at and how to best convey it in the target language. And though a great deal can be found on the Internet, some particularities will remain obscure: No virtual tour will give you a clear view of roof constructions, palace kitchens, gates or stabling facilities. Which hardly ever presents problems; descriptions usually allow for general wordings. Bring up the Bodies, or rather its protagonist Cromwell, does not. By the time I started grumbling about the ‘preposterous lack of information on the Internet’, I thought it best to go over and have a look myself, and if possible, to discuss everything that still puzzled me about the text with Ms Mantel. So I (timidly but hopefully) applied to the Dutch Foundation of Literature for a travel grant, which met with generous approval.

For the past year I have had the good fortune to legitimately engross myself in what is to me the most compelling of novels, translating Hilary Mantel’s Bring up the Bodies, the sequel to 2009 Booker Prize Winner Wolf Hall. The most compelling novels do have a habit of providing ample scope for research, leading you on winding paths outside the pages of the book in order to know what exactly an author is alluding at and how to best convey it in the target language. And though a great deal can be found on the Internet, some particularities will remain obscure: No virtual tour will give you a clear view of roof constructions, palace kitchens, gates or stabling facilities. Which hardly ever presents problems; descriptions usually allow for general wordings. Bring up the Bodies, or rather its protagonist Cromwell, does not. By the time I started grumbling about the ‘preposterous lack of information on the Internet’, I thought it best to go over and have a look myself, and if possible, to discuss everything that still puzzled me about the text with Ms Mantel. So I (timidly but hopefully) applied to the Dutch Foundation of Literature for a travel grant, which met with generous approval.

Visit

During my visit with Hilary, my curiosity got the better of me – but I suddenly realise it may sound strange that a not altogether inexperienced translator English-Dutch, having access to a heap of dictionaries and other resources, should need the cooperation of someone who hardly knows a word of Dutch. In case it does (sound strange), let me give you a general idea of the sort of query that makes up a translator’s list:

On your way, phantom: his [Cromwell’s] mind brushes it before him; who can understand Wyatt, who absolve him?

The grammatical construction of ‘who can understand Wyatt, who absolve him?’ suggests the second ‘who’ to be identical to the first, and ‘him’ to be Wyatt. Which would plead for ‘absolve’ to point to the Dutch meaning of (Catholic) absolution, forgiveness. But. It is only a suggestion. The grammatical construction can be read differently: yes, the second ‘who’ will be identical to the first, but ‘him’ could just as easily refer to Cromwell. And if that is the case, ‘absolve’ could just take on a completely different Dutch meaning, that of ‘releasing someone from his/her responsibility’. The context allows for both interpretations. Thomas Cromwell has been asked by Wyatt’s father to look out for Wyatt, a request he, Cromwell, takes very seriously. He feels the responsibilities of a father towards Wyatt. At which point, you will understand, I really, really needed Hilary to tell me who is ‘him’.

Jelly dishes

Back to Hilary, then. (‘Him is Wyatt, and the meaning should be that of (Catholic) absolution.’) She had just shown me an anecdotic bit of history from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, where in 1510 Cromwell is bid to pave the way to the Pope’s court for a guild delegation on the mighty quest of obtaining the renewal of two ‘pardons’ (dispensations perhaps from Lenten austerities or some such) from Pope Julius II. Knowing ‘how the Pope’s holy tooth greatly delighted to new fangled strange delicates’, it came to his, Cromwell’s, mind to prepare jelly dishes. Accompanied by English music, jelly dishes in hand, he advanced on the Pope, who in his delight stamped both pardons ‘without any adoe’.

It made me marvel about two things: on the one hand the way she had taken the story and deducted from it pieces of the puzzle that is Cromwell’s (early, personal) life, and constructed a highly credible, even perfectly likely version of events; his speaking Italian, his knowing his way to the Pope’s court, his being asked by a trade delegation to intervene on their behalf, his knowing how to prepare jelly dishes ‘after the best fashion’ and how that must have come to be. And on the other hand the intimate glimpse she gave me of her writer’s reality, the keen awareness with which she has to evaluate tidbits of information, the meticulous care with which she constructs a whole fictional world, using every tool available, be they textual (grammatical tense, focalisation) or more cultural (references to other texts, pointers to a collective memory, to shared customs and eccentricities). It felt like getting a wonderful present, because it was beyond what we had set out to do, which was no more than to solve a few queries.

Translator’s reality

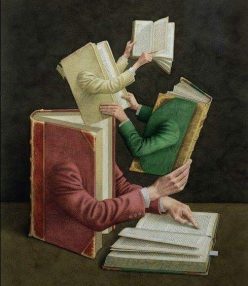

In return I talked of a translator’s reality, the translator’s fascination with solving the clash of two bodies of decidedly different conventions, breaking down both bit by bit, investigating and comparing each bit in order to reconstruct as well as can possibly be the original fictional world, so it can be opened and lived in by another audience.

But I am not very good at expressing the things that move me deepest, not in spoken words, not when they have to be spoken on the spot, with thoughts racing ahead and getting into a hopeless tumble. I wondered if I had been clear at all. Most of all I wondered what it meant to her, having her reality cross that of the translator. Would she in fact prefer not to be involved when her work goes across borders and starts an adventurous (or downright perilous) new life? On this occasion it would certainly have spared her the headache of a thousand questions, let alone the time spent to explain what on occasion must have seemed quite obvious to herself. What would any writer want from his/her translator in an ideal world?

As I said, my curiosity got the better of me, so in the end I just went ahead and asked. And Hilary being Hilary, she responded readily and wholeheartedly with an essayish piece on author-translator collaboration. If I dare, I think I will ask other writers too.

Mooi stuk! Leuk, zoals je beschrijft welke keuzes je moet maken en hoe de schrijfster reageert op vragen. Een ideale situatie, lijkt me, die alleen maar positieve invloed kan hebben op de vertaling die je maakt 🙂

Hé, Ine, leuk verhaal. En waar kunnen wij dat “essayish piece on author-translator collaboration” lezen?

Dank! @ Lidwien: Als het goed is, staat Hilary’s reactie nu boven aan het lijstje ;-). Ik had haar gevraagd om met die vragen in het achterhoofd iets voor ons blog te schrijven. Geweldig dat ze dat ook heeft gedaan. Ik heb haar de links toegestuurd, zodat ze eventueel kan reageren op wie er eventueel reageert, vandaar dat hier in enen een stuk in het Engels verscheen.

@ Hennie: ja, het is heerlijk als een auteur zo open staat voor vragen en gepuzzel. (Zou dit dan ook maar in het Engels moeten? Rather wonderful when a writer is so open to questions, it certainly helped!)

Deze stukken van u en Hilary Mantel zijn voor ons geen gemakkelijk Engels. Wij lezen Wolf Hall in het nederlands. We kwamen op het idee door de Tudors. Daarom willen we graag alles erover lezen aan meer informatie voor de leeskring. Ook over het boek Henry. Uw eerste stuk over het vertalen van de boeken schreef u ook in het nederlands en dat was interessant. Gaat u dat met deze stukken ook doen? Dat zou superfijn zijn!

Hallo Joke en Liesbeth,

Leuk, die interesse, dankjewel. Het is ook een ontzettend boeiende periode, dat tudortijdvak, het heeft eigenlijk alles: de politieke verwikkelingen en de romantiek, en dan in zoveel lagen. In dit stuk ben ik wat meer ingegaan op de relatie tussen schrijver en vertaler en omdat Hilary ook zou bijdragen, heb ik dat in het Engels gedaan. Maar natuurlijk schrijf ik met liefde in het Nederlands een stuk over het vertalen van Het boek Henry! Laat me er een weekje op broeden, maar ik kom erop terug.

Begrijp ik goed dat jullie het boek in de leeskring gaan behandelen? Ik zou het leuk vinden om tzt te horen hoe dat is gegaan, en omgekeerd, als jullie opmerkingen of discussiepunten hebben, dan kun je altijd contact opnemen, eventueel via de uitgeverij.

Hartelijke groet,

Ine

Hallo Ine

Wat fijn dat u antwoord geeft! Maar weet u, u hoeft voor ons niet de moeite te doen een heel nieuw stuk te schrijven. Sorry als u dacht dat wij dat bedoelden, onze fout.

Wij willen veel liever in het nederlands deze stukken lezen. Wilt u ze nog vertalen alstublieft?

Wij willen ook graag weten wat Hilary Mantel over vertaalwerk schrijft. Daar letten we nooit erg op en dan kunnen we het daar deze keer ook over hebben.

We hebben het in googlevertalen geprobeerd maar het word dit: “Net als veel Britten van mijn generatie, ik ben bijna een Eentalige. Ik leerde Frans op school, maar leerde zo slecht dat ik geen vertrouwen hebben in het spreken of het lezen van de taal had, in hoofdzaak, het werd geleerd om mij als een uitgestorven taal, zoals het Latijn, en geen bevestiging werd gemaakt van het feit dat, binnen zichtbare afstand van onze kust, werden miljoenen tevreden Fransen en vrouwen kletsen.” Nou u begrijpt daar hebben we niets aan!

Als u hier de echte vertaling zet laten we u natuurlijk achteraf weten hoe het is gegaan. Via de uitgeverij als u dat liever wilt.

Bij voorbaat veel dank en hartelijke groet

Liesbeth ook namens Joke

Hallo Joke en Liesbeth,

O lieve help, nee, haha, wat een ramp, zo’n Google-vertaling. Hoewel, voor ons niet, natuurlijk, het is fijn te merken dat mensenwerk voorlopig nog wel even mensenwerk blijft.

Het was even een kwestie van tussendoor de tijd vinden om Hilary’s stuk te vertalen, maar ik ben ermee bezig (de redactie moet ook even tijd vinden om tussendoor te corrigeren, natuurlijk) en het komt eraan. Wat mijn stuk betreft, denk ik dat het zeker voor leeskringen leuker is om hier over concrete vertaalstruikelblokken en verwijzingen te lezen, maar als jullie contact met me opnemen, stuur ik jullie met plezier een vertaling van het bovenstaande artikel.

Hartelijke groet,

Ine